ORCİD: 0000-0003-0796-8834

Abstract: The aim of this study is to reveal the holistic administration model of social policy actors in a city with the case of Esenler district in Istanbul. In this respect, it is aimed not only to determine the individually social policy functions of each actor, but also to model what kind of an administration model should be followed in terms of social policy in a city. The scope of the study for this purpose is the social policy implementations of social policy actors for social policy recipients in Esenler District of Istanbul. In this context, the study deals with Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services’s (ACSHB) district unit of the central government, the Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundations (SYDV), the local district municipality and the NGOs of the district. The field part of the study was conducted between February and March 2018. Semi-structured interview form and observation technique were used in this study. A total of thirty seven (37) people (participants) were interviewed. The model that emerged in this framework has three basic principles: i) compassion, justice and rightness. ii) There are some obstacles in the implementation of these basic principles: the ones originating from the legislation, the determining mechanism, the budget issue, the institutional ground and the personnel status. iii) In order to overcome barriers, the density center for social policy recipients and the gravity center are proposed for the social policy actors who implement social policies.

Bir Şehrin Sosyal Politikalarını Yönetmek:Keywords: Social policy, Istanbul, Esenler, administration.

İstanbul Esenler İlçesi Üzerinden Modelleme

Öz: Çalışmanın amacı, İstanbul ili Esenler ilçesi örnekliği üzerinden bir şehirde sosyal politika aktörlerinin bütüncül yönetim modelini ortaya çıkarmaktır. Bu minvalde her bir aktörün müstakil sosyal politika işlevlerinin ortaya konulması ile yetinilmeyip, bir şehirde sosyal politika anlamında nasıl bir yönetim modeli izlenilmesi gerektiği hususunda model çıkarılması amaçlanmaktadır. Bu amaç doğrulsunda çalışmanın kapsamı, İstanbul İli Esenler İlçesi’nde sosyal politika aktörlerinin sosyal politika alıcılarına yönelik sosyal politika uygulamalarıdır. Bu bağlamda çalışma, sosyal politika aktörü olarak merkezi yönetimin Aile, Çalışma ve Sosyal Hizmetler Bakanlığı (AÇSHB) ilçe birimi, Sosyal Yardımlaşma ve Dayanışma Vakıfları (SYDV) ile yerelin ilçe belediyesi yanında ilçe STK’larını ele almaktadır. Çalışmanın alan/saha kısmı, 2018 yılı Şubat-Mart ayları arasında gerçekleştirilmiştir. Çalışmada veri toplama türlerinden yarı yapılandırılmış mülakat formu ve gözlem tekniğinden yararlanılmıştır. Toplamda otuz yedi (37) kişi (katılımcı) ile görüşülmüştür. Bu çerçevede ortaya çıkan modelin i) merhamet, adalet ve doğruluk olmak üzere üç temel ilkesi bulunmaktadır. ii) Bu temel ilkelerin uygulanmasında bazı engeller bulunmaktadır: Mevzuattan kaynaklı olanlar, tespit mekanizması, bütçe meselesi, kurumsal zemin ve personel durumu. iii) En nihayetinde, engelleri aşmak için sosyal politika alıcıları için yoğunluk merkezi mantığı ve bu alıcılara yönelik uygulamaları yapan aktörler için de ağırlık merkezi önerilmektedir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Sosyal politika, İstanbul, Esenler, yönetim.

Introduction

The administration of a city requires many variables to be considered. One of these variables is social policy. Social policy is a variable that has both narrow and broad meaning. Narrow meaning of social policy is only directed at working life and is an effort to regulate worker-employer relations in working life. In the broader sense, social policy is in the context of the solution of all the social problems in non- working life; in this respect, all of the disadvantaged groups are interest to the broader sense of social policy. Besides its narrow and broad meanings, social policy has the transnational meaning. Here, there may be social policies with actors that cross country borders.

On the other hand, social policy has different actors. On the most basic, there is a central government (state) actor. On the one hand, the state is both a legislator and a regulator of worker-employer relations in working life, and a mechanism to overcome all social problems including disadvantage. In this respect, the state has steps in the narrow and broad sense of social policy. The municipalities, which are a second actor of social policy, are more broadly engaged in social policy activities; there are workers of municipalities and also the municipality is the public employer. In this respect, the municipalities have sides to the narrow meaning of social policy. However, municipalities’ efforts to solve the problems of the wider social groups such as poor, disabled, elderly, women, children and youth are seen in the fields of activity of the municipalities. Apart from these two actors, there are NGOs as weak actors. Employers sometimes contribute individually and sometimes as corporate social responsibility. Therefore, a total of four actors of social policy emerged.

This framework of social policy, of course, applies to each city. Each city has narrow or wide scope of social policy areas for implementation. Naturally, the social policy implementations are also observed in Turkey’s cities, too. The actors of these practices are also central government and municipalities with central government units in the cities. NGOs and, in some cases, employer contributions also appear. Here is an important question comes to mind: While the social policies of these cities are carried out by different actors, what is their administration? In other words, what is the social policy administration of a city in general, and how should it be?

In this research, it is aimed to answer this basic question. Response effort will be in the form of creating a model from the Esenler district of Istanbul. The field study part of such an effort is a semi-structured in-depth interview with the administrators of the social policy actors in Esenler and the field staff on social policy.

In this context, firstly the literature related to the subject is included in the study. Since the direct sources on the subject are very few, the screening of indirect sources is presented in a concise way. Then, the social policy model of administration in a city for social policy actors taking into account the social policy recipients through the findings of the field research is presented.

General Framework

Related Literature in Brief

Besides the literature on social policy actors, the literature on social policy administration is important in terms of seeing the place covered by the subject. Although resources related to social policy actors are very numerous, there are few sources for administration of social policy, and indirect sources rather than being directly connected to the subject.

Literature on Social Policy Actors

As the actor of social policy, there is basically central government. In addition, local government/municipality and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and private sector/enterprises also act as social policy actors. In this respect, various studies are carried out on social policy actors. The majority of these are in the context of public actors. Among the public actors, studies on central government and local government actors are close to each other. Studies on NGOs are not few and have found a certain ground, but studies on the social policies of the private sector have been the product of recent periods and thus are few.

In the case of a central government actor in social policy, the literature is mostly shaped around “social state”, “the welfare state/regime”. Turkish literature is mostly based on “social state”; international literature is more around the “welfare state/regime”. The issue of the social state is particularly intense in Turkish literature; but there are also foreign (non-Turkish) sources. These sources are distributed in the form of certain sub-topics. Some sources focus on the mentality and system of social state, some resources are related to what the social state is, some resources are about the rise, fall or end/death or future of the social state. Some sources are in the context of Turkish historical experience of the social state, and some are the discussions whether the social state in Turkey is sufficient or not. Some of the sources relate to a subject in the context of the social state. Very few sources also consider the social state as a separate or inter-country comparison.5 Although studies on the welfare state/regime are predominantly international literature, Turkish sources are increasing day by day. In this framework, the main source is Esping-Andersen’s (1990) work “Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism”, in which he classifies the welfare state(s) in the form of social democrat, liberal and conservative. On the other hand, there are many studies on typologies related to welfare state/regimes. Some of these are typologies, their nature, and debates around particular topics. Some of them are about countries in typology particularly. Some are on a comparison of multiple countries of the same typology. Some of them are about the place of countries within typology. Some studies are on Turkey’s place in the typology, too. These are all around the specific sub-topics of social policy and are generally written in a critical context.6

The second actor is local government. Local government is a concept representing all local units, but the concept of local government in Turkey is also used by the scope of the municipal activities. It is not difficult to find both in international and Turkish literature; especially in recent years, there has been an increase in the number of publications about the issue. Considering the area of local governments/municipalities, some of these studies naturally take shape around important sub-issues such as migration, cities, urbanization, urban management/governance. Some studies focus on the nature, importance and effectiveness of local governments in general. Some studies are jointly addressed to the welfare state on issues such as economic/financial in particular, overcoming the crisis of the welfare state, and reforming the welfare state. Certain studies are also about the social (welfare) policies of local governments. It is about local governments/municipalities in Turkey and their social policies. Some of these are related to special concepts such as “social municipality”, “welfare municipality” and “social entrepreneur municipalities”. As can be seen, it is not possible to mention the existence of an independent study on social policy administration of local governments; however, there may be several studies in the context of “governance”.7

Another actor of social policy is NGOs. In general, the literature on civil society is broad, followed by an expanding literature on the social policies of NGO actors. Studies on civil society itself and its general importance are not difficult to find. There are also studies that demonstrate the relationship between civil society and several variables such as globalization and neo-liberalism. In addition to these, there are also studies that deal with the relationship between civil society and social policy in a general sense. In addition, studies on the presence/activity of civil society in certain areas of social policy are also prominent. These include NGOs’ separately struggle against poverty, activities for migrants, steps towards children, efforts towards the disabled and the elderly, presence in education and health, importance for women, post-human and natural disasters, supports for homeless and addicts. In addition, there are studies that deal with multiple social policy issues in the context of NGOs.8

One of the social policy actors is also the private sector. The private sector actor can also be referred to as businesses; ie businesses instead of private sector can be used. The area covered by the private sector/businesses actors is very small within the social policy literature. The literature on the concept of social policy itself is scarce. Some of these few studies address the general nature of the social policies of the businesses themselves; and some of them are about the practices of the businesses as social policy actors; very new and few studies are around the “social investment state”, which is a mixture of social state and private sector or around the “social enterprise” in the sense of a mix of social and business.9 On the other hand, the social policies of the businesses have a wide range of “social responsibility”, and the literature on concept of social responsibility is broad. Some of them are of general conceptual or theoretical feature, some others are about social responsibility issues in poverty and similar areas, some of which are on topics in working life axis. Some of them are about the developments in Turkey, and some are in the context of projects in implementation.10

Literature on Administration or Governance of Social Policy

The coverage of the social policy actors in the literature is briefly summarized. What is the level of studies where more than one social policy actor is considered? Here, first of all, the issue should only be addressed in the context of social policy. At this point, it is possible to find “general” studies about the co-operation of the actors. There are also studies on the cooperation of actors in the “field” of social policy.11

On the other hand, what is the situation of the sources where social policy actors are handled together through social policy administration or governance? There are few theoretical and general studies on social policy administration/governance, some of which are about administration or governance in relation to sub-topics of social policy. Along with the central government, there are few studies on the involvement of private sector and civil society in participatory administration and governance in the field of social policy. Only a small amount of resources are found in the administration of social policy through its central-local relationship. There are also sources in which central government and NGOs deal with issues of governance to overcome problems.12

There are also studies where NGO is handled at the center in administration together with other social policy actors. Works can also be seen about partnerships between NGOs and local governments in the context of administration/governance. Studies on the work of NGOs with the private sector can be seen in the area of social policy.13

Field Research: Esenler Case

The aim of this study is to reveal the holistic administration model of social policy actors in a city with the case of Esenler district in Istanbul. In this respect, it is aimed not only to determine the individually social policy functions of each actor, but also to model what kind of an administration model should be followed in terms of social policy in a city.

Of course, the method used in carrying out a research is of great importance. A single interview technique was not followed in the study. The reason for this is that most of the interviews were conducted one-to-one, but some interviews were conducted with the combination of the researcher group and the interviewees were single. The interviews were conducted using semi-structured interview technique which is frequently used as a qualitative research method. After determining the subject of research and data collection technique, the application area, ie the universe of the research is determined. In this framework, “aiming sample” was preferred in determining the interviewees. The subject of the study is related to the “administration”, and the interviewees are administrators and the field administrators connected with the administrators.

The scope of the study is the social policy implementations of social policy actors for social policy recipients in Esenler District of Istanbul. In this context, the study deals with Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services’s (ACSHB) district unit of the central government, the Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundations (SYDVs), the local district municipality and the NGOs of the district.

Another limitation in the study, which is limited to the experiences (information) of the interviewees, is related to the disadvantages arising from the structure of the interview technique. According to this, there must be technical experience in order to provide dominance the process, to give confidence to others, to detail with new questions and to obtain objective information. On this topic, there were some points where subjective opinions were dominant in the interviews and the researchers had difficulty in gaining details. For this reason, the information obtained by the researcher should be supported by questions such as “What do the interviewees say and what they mean? What and how do they perceive? What conditions cause it to be perceived?”, and the answers may have to be searched. On the other hand, the study is limited to Esenler district of Istanbul. In the selection of Esenler as working area, on the one hand the City Thought Center for Esenler Municipality’s extensive opportunity for Esenler was effective, on the other hand Esenler’s social, economic and cultural texture seems to be favorable for social policy. Moreover, since there are almost no studies on social policy administration of a city in terms of holistic view, there may be some difficulties and limitations caused by being the first study; so there were some difficulties especially due to lack of literature.

In terms of time, the field part of the study was conducted between February and March 2018. In this respect, semi-structured interview form and observation technique were used in this study. For the preparation of the questions in the interview form, a preliminary phase was prepared for the persons/institutions who may be the actor in the relevant field and about forty (40) questions were prepared in order to obtain in-depth information. However, during the interviews, in order to make the information transfer and communication processes more healthy, the questions were combined in essence and reduced to about fifteen (15) questions. Thus, the interviews were thought to be more efficient.

Table 1- Interview Participant List

|

|

Institution |

Status |

Interview Date |

|

Participant 1 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

28.03.2018 |

|

Participant 2 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

14.02.2018 |

|

Participant 3 |

Municipality |

Fieldworker |

14.02.2018 |

|

Participant 4 |

Municipality |

Fieldworker |

14.02.2018 |

|

Participant 5 |

Municipality |

Fieldworker |

19.02.2018 |

|

Participant 6 |

Municipality |

Fieldworker |

19.02.2018 |

|

Participant 7 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

22.02.2018 |

|

Participant 8 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

5.04.2018 |

|

Participant 9 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

28.02.2018 |

|

Participant 10 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

22.02.2018 |

|

Participant 11 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

22.02.2018 |

|

Participant 12 |

Municipality |

Administrator |

20.02.2018 |

|

Participant 13 |

Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services |

Administrator |

26.02.2018 |

|

Participant 14 |

Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services |

Fieldworker |

26.02.2018 |

|

Participant 15 |

Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation |

Administrator |

5.04.2018 |

|

Participant 16 |

Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation |

Administrator |

6.03.2018 |

|

Participant 17 |

Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation |

Fieldworker |

6.03.2018 |

|

Participant 18 |

Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation |

Fieldworker |

7.03.2018 |

|

Participant 19 |

Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation |

Fieldworker |

7.03.2018 |

|

Participant 20 |

Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation |

Administrator |

6.03.2018 |

|

Participant 21 |

NGO |

Administrator |

20.02.2018 |

|

Participant 22 |

NGO |

Fieldworker |

20.02.2018 |

|

Participant 23 |

NGO |

Administrator |

2.03.2018 |

|

Participant 24 |

NGO |

Administrator |

1.03.2018 |

|

Participant 25 |

NGO |

Administrator |

12.03.2018 |

|

Participant 26 |

NGO |

Administrator |

14.03.2018 |

|

Participant 27 |

NGO |

Administrator |

20.03.2018 |

|

Participant 28 |

NGO |

Administrator |

12.03.2018 |

|

Participant 29 |

Neighborhood |

Mukhtar |

13.03.2018 |

|

Participant 30 |

Neighborhood |

Mukhtar |

8.03.2018 |

|

Participant 31 |

Neighborhood |

Mukhtar |

13.03.2018 |

|

Participant 32 |

Turkish Directorate of |

Imam |

8.03.2018 |

|

Participant 33 |

Turkish Directorate of |

Imam |

28.02.2018 |

|

Participant 34 |

Turkish Directorate of |

Imam |

1.03.2018 |

|

Participant 35 |

Ministry of National Education |

Administrator |

14.03.2018 |

|

Participant 36 |

Ministry of Health |

Administrator |

15.03.2018 |

|

Participant 37 |

NGO |

Administrator |

21.03.2018 |

On the other hand, in accordance with the structure of the semi-structured interview form, the detailed information method was applied according to the course of the interviews. A total of thirty seven (37) people (participants) were interviewed (Table 1). Interviews with the participation of at least two researchers have been recorded, and then they have been turned into text by a deciphering process. A total of 2307 (two thousand and three hundred and seven) minutes were recorded and 643 (six hundred and forty-three) pages of the interviews were created as a text database. In addition, this database allowed researchers to conduct a strong content analysis with the observation made.

Research Findings: Basic Principles, Possible Obstacles and Overcoming Them

If it is desired to prepare a model for social policy administration of any city, it should be known that it cannot be a model without a principle, and therefore the basic principles of social policy administration in a city should be laid. Certain principles have emerged from research findings. However, principles alone are not enough; research findings mention obstacles, too. A framework for overcoming these barriers is also needed. At the end of these processes, a model can be put forward.

Basic Principles of Social Policy Administration in a City

Based on the findings of the research, it can be mentioned that there are three (3) basic principles in the form of compassion, justice and rightness which nourish/complement one another in social policy administration of a city.

Compassion Based Grounding

The steps of social policy actors towards social policy recipients require compassion based grounding. This is the first principle that social policy actors should not miss when ruling cities. This principle requires a number of progressive steps in administration.

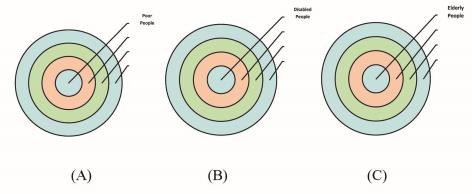

Figure 1 - Steps of the Principle of Compassion

As can be seen from Figure 1, the first of these steps is to center the “no matter what happens, human” fact of the social policy recepients while ruling the city. The fact that one of the interviewed executives (Participant 1) declares that he considers his administration as the “human revival” is the expression of this fact. Therefore, if there is this principle, there can be no account other than “being a needy person”. As stated by another participant (Participant 15), the profit-loss account cannot be made in the social state and it is the “duty” of the administrators of the city to meet the needs of the people concerned. This task/principle (compassion) should offer such a wide ground that people in need should not say “I hesitate from and could not go to” to administration authorities to resolve their needs (Participant 4). If necessary, this compassion principle means that the administrators are mobilized to meet the necessities of the needy with their own special means when the institution is not sufficient (Participant 5). In this way, the issue of social policy administration in the city is to be in “if the needy is human, this is enough” approach. As a matter of fact, as one participant from NGOs, one of the city’s actors of social policy administration, is uncomfortable (Participant 37), granting scholarships only to students from their hometowns is against the principle. Similarly, not serving “a needy person” who was a guest of the Esenler and who, for example, was ill, but whose residence was Tokat, was against the principle of compassion, as one of the participants (Participant 10) stated. As a more extreme example, it is an extension of the principle of compassion for the former convicts to be in need of support.

The second step in the embodiment of the principle of compassion in a city’s social policy administration is related to possible grounds for discrimination. Although “human” and similar many expressions can be seen in discourse, in practice there may be inhumane “discrimination”. This danger is also mentioned in the interviews. For example, one of the administrators reveals that they do not fall into the ground of discrimination by saying “we are helping them as we support our poor” (Participant 8) in relation to the Syrians in Esenler and that they only take steps according to “the needy person”, that is, the principle of compassion. Similarly, with the statement of a participant from imams (Participant 32) in the Esenler, it should be accepted as a duty not to be discriminatory against an “addicted” child on the street and to center on the fact that he is a human and “to save him”.

The third step in showing the existence of the principle of compassion in the social policy administration of the city is to continue the support without sacrificing the principle of compassion in order not to suffer the majority that does not exploit or lazy even if some of the social policy recipients exploit the principle of compassion. Accordingly, as one of the participants stated (Participant 15), it is necessary to know and acknowledge that social policy practices for some of the social policy recipients are “open to abuse”; hence “because the exploitation exists, the door of charity cannot be destroyed”. In this respect, what is to be done is to help them to the fullest because of the large number of people in need, even if they are abusers (Participant 8). Otherwise, to cut off the support of all social policy recipients because there is abuse means to cause homeless to roam in the streets (as in the USA) (Participant 15). The abuser has also a family. Therefore do not support or interrupt existing support due to the abuser will also make many families difficult position (Participant 28).

The fourth step of the embodiment of the principle of compassion in a city’s social policy administration is related to its priority. In other words, if human beings are in need, they should be able to benefit from social policies as a matter of compassion, but which should be the priority in case of any conflict or under normal circumstances? According to this, the emergency case should be prioritized “without waiting for a moment” (Participant 23). It is not important who the emergency case is about; it may be a child, an elder, an ex-convict. “It’s human and it’s an emergency.” In some cases, being disabled or elderly may require priority. In general, these “some cases” may be related to health. For example, being bedridden and therefore not being able to work on its own requires priority (Participant 10). A priority here is “for emergency points outside the city”. Without neglecting the needy of its own city, the needy people outside the city should be able to find a place in the priority list. The fact that the director of a NGO in Esenler (Participant 24) stated that they helped the Earthquake victims in Van, that they have five water wells in Somalia, or that they had given serious aid to Halabja are about this context.

The fifth and final step of the principle of compassion in the administration of a city’s social policy is to make maximum effort to ensure that social policy recipients are not deciphered. What is meant here is that there is no stigmatization or humiliation; having a mechanism functioning based on a kind of “secret cube” (Participant 33). In this step, there are two aspects: “determining” social policy recipients and then “implementation” part towards those determined. The first aspect is generally related to the social enquiry conducted to determine. It is important that an administrator (Participant 8) declares his/her counsel/warning to field workers who will conduct social enquiry: “Consider the victimisation of these people when you go for social enquiry, and treat them without hurting.” The fact that the real needy “cannot declare his/her necessities” (Participant 5) also shows the importance of this sensitivity more clearly. At this point, it is important to pay attention to the fact that the car used by the social enquiry team is just enough to help to understand that it comes from the institution (Participant 14). With the same logic, it can be considered as a necessity that the “social worker’s attire should be in such a way as to help to understand that it came from the institution” (Participant 17; Participant 13). Otherwise, the fact that the social enquiry team go to the scene for determination as a flamboyant way can open the door for injuring, stigmatization and even humiliation the needy. However, “even this amount of visibility” causes the neighbors of the household to come to the household and may cause some to be offended (Participant 16). Therefore, it is important to create “an isolated ground” from the environment as much as possible in determining mechanims.

The second aspect of the mechanism, which operates under the confidentiality, the “implementation” part towards social policy recipients after it has been determined. This may sometimes involve preferring in-cash social assistance instead of providing in-kind assistances like food and similar support (Participant 2). For example, the social market has some benefits like socializing, but only the poor are involved in the market (Participant 1). This means being “visible” of social policy recipients as bringing supplies to someone’s home. Therefore, it is also dangerous in terms of confidentiality when the logos of the institution and the clothing company car stands in front of the needy person’s house; and this is a stigma. For this reason, opening a bank account for the person in need, and depositing the amount of cash social assistance there is important for the confidentiality of the social policy recepient (Participant 15). The problematic issue here is that social policy practices are announced or published in the form of newsletters, social media and web pages. Such a step, of course, carries the risk of stigmatization for social policy recipients. To be explicitly stated, social policy recipients should not be the “wall flower” (Participant 2). If there is nothing directly about the reciepients in the photos, there is no problem. Announcements on social policy practices are not a problem, but it is a problem that one of the recipients has a photo in the content of the announcement. Expression of a participant like “the only thing we put in our bilbord is to say that there is an intelligence course in the mother-child center, come and join us” (Participant 3) indicates that this sensitivity is observed. However, it is also stated that there are problems from time to time (Participant 14). Especially for the NGOs, “visibility of the implementation” is a kind of document to find financial support for what is to be done later; and “all associations must do this” (Participant 28). Due to this problem, there are participants who consider it more appropriate not to help. Apart from all these, it is sufficient to enforce the law on the confidentiality of personal data (Participant 15).

Justice Based Applications

Justice is the second principle that complements and balances the first principle (compassion) in which social policy actors administer the city in the context of social policy. The principle of justice is necessary for a sound order in the practice towards social policy recipients. The existence of this principle also requires concrete steps.

Figure 2 - Steps of Justice Principle

According to Figure 2, one of the concrete indicators of the principle of justice in a city’s social policy administration is preventive social policy measures; because the main objective is not to become a social policy recipient. In this sense, preventive social policy measures such as practices in the field of education, which are ways of not being unemployed before being unemployed; to be meticulous before or after childbirth in order not to be disabled; not being exposed to violence; prevent divorce and thus ensure that children do not remain in a fragmented psycho-social vortex or to treat family policies seriously and wholly to prevent the elderly from being considered problematic are indicators of the principle of justice. Perhaps the prevention at the center of all preventive measures is related to the family because every person is born in a family and is a part of the family, good or bad. Therefore, every step towards protecting and strengthening the family will be an important preventive social policy step affecting all other social policies. In this respect, it is reasonable examples to conduct “seminars to inform families” with expert counselors, sociologists and psychologists. As the spatial constructs of these, more extensive studies under names such as “knowledge and wisdom house”, “youth center” or point shootings such as “host families” (Participant 9) are also important for the prevention. Similarly, “vocational training centers” are also important in order to eliminate the unqualification that arises when there is no course or open education record, which is the minimum requirement to employ a person, and thus to ensure employability (Participant 35). Moreover, instead of implementing social policy practices after the emergence of health problems, for example prior to problems, “sample analysis in terms of water hygiene in schools at specific intervals” (Participant 36) is also in the preventive social policy steps. To bargain with families who are one of the reasons of children begging in the streets and to enroll them in schools, to include them in the education life by paying money to their families (Participant 13) and thus in addition to providing employability, preventing them from falling into bad roads (addiction, crime, etc.) is another example of preventive social policy.

The second step in terms of the principle of justice in a city’s social policy administration is that there may be needy (ie intervening for social policy recipients) for one reason or another despite all the preventive social policy steps (ie the first step). In this respect, the main issue of justice is the right to eliminate the needy of every human being in need. There are two issues here. The first point is the “determination of the number” of social policy recipients. The number of social policy recipients should be determined and updated in each settlement. If it is an ambiguous, hypothetical, approximate, estimated ground such as “There are about 7 thousand disabled people in Esenler. Maybe this number is less than the official numbers, but there are some who have not yet been identified and who still have not applied for disability assessment” (Participant 26), then justice will work for some social policy recipients while it will not work for another because another part is not in number. With the expression of another participant (Participant 27), there is “definitely not reached one”. Here, the other point that is important in order to make clear the number is to make clear “who” the social policy recipients are. Finally, both the number and the recipient types should be updated at the same time.

The third step is about accessing to applications. If justice is desired in a city’s social policy administration, “the channels” of needy to be social policy recipients should be open and well-functioning. This step also shows that the second step alone is not sufficient; because even if the potential number of social policy recipients is clearly set forth, it is obvious that the failure of these recipients to access the system will be a problem in terms of the principle of justice. “There are areas where Turkey hasn’t touched it yet” statement of an administrator (Participant 15) is also related to this problem. Not touching or failure to touch, in one aspect, means that potential recipients are “not aware” (Participant 7). While social policy actors have corporate social media accounts, the lack of active web pages (Participant 28) should be recorded as a serious deficiency, but SMS or one-to-one phone calls can fill this gap (Participant 11).

Once the access situation is resolved in some way, the fourth step for the principle of justice in a city’s social policy administration is the speed in decisions. The net determination of the number and the access of the determined ones to the system alone are not sufficient; additionally, social policy executives should operate fast decision-making processes that do not suffocate the procedure because justice, which is not manifested in time, will not be justice in the true sense. Expression of a participant like “I think I’ll be back for a week, but sometimes there are delays due to the project” (Participant 28) indicates this risk. According to one participant, situations such as “abundant form and orientation to right and left” are “bureaucratic oligarchy” (Participant 9). The situation may be more stringent for some social policy recipients such as people with disabilities (Participant 26). The statement of another participant, such as “It results in a maximum of 15 (fifteen) days. In case of emergency, it is answered within 7 (seven) days. As we meet every thursday, we immediately make immediate decisions at those Thursday meetings” (Participant 16) related to the applications indicates that the process can be run quickly.

On the other hand, the fifth step for the principle of justice in social policy administration is not to have clientelistic or patronage ground in the applications. This is a matter that needs to be considered both in decision-making and the applications. It is normal that “politics and social policy are intertwined” (Participant 1), but independence from political “pressure” is essential in decision and practice. Expressions such as “there is absolutely no such pressure” (Participant 8; Participant 16) are frequently mentioned. Similarly, the statement of “my brother’s daughter applied for a scholarship; there was no help to her” (Participant 5) stands out as a more concrete example. According to some of the participants (Participant 13), it is considered fair to take decisions in the “commission”. Here, even if there is no direct pressure, it may be a matter of prioritization coming from communication by way of request (Participant 11). This, of course, is against justice and should be avoided. The issue is more important for administrators who use initiative (Participant 27); they must use their initiatives for rights and justice.

The sixth and final step is not wasting. The use of resources in a city’s social policy administration is important, but the use of resources without waste is more important for the real needy not to be victimized. This is directly related to the provision of the whole of the five steps listed for the manifestation of justice. If there are preventive social policy steps, there will be no need for large costs due to interventionist social policy. In cases where interventionist social policy steps are needed, identifying the number and determining the recipients will prevent unnecessary expenditure. It is also necessary for the recipients to have access to the system and to make use of the system as fast as possible and without clientalism. In these steps, the attempts of social policy recipients such as “you must to help” (Participant 11), ie potential recipients’ efforts to active the compassion vessels of social policy administrators should be balanced with the sword of justice. Therefore, as one participant said, if you cannot distribute benefits in justice, what is the meaning of doing this work (Participant 3).

Rightness Based Supervision

Without supervision, it is not possible to fully understand whether the practice is fair or not. The supervision must also be with the correct method. Therefore, the supervision with the correct method is important in order to see whether the practices are fair. This supervision means interventions with legal sanctions.

A second issue is that the main objective of supervision should be to make it sustainable. According to this, it is necessary to see whether applications can enable social policy recipients to stand on their own feet. The supervision of families who are given assistance through visits to their homes is an example of this (Participant 16). These home visits should be more than once if necessary (Participant 18). Currently, there is a requirement to monitor the support of some actors in the public sector every 6 (six) months (Participant 13). Thus, during the visits, those who have improved their previous need are re-evaluated (Participant 16). If, for example, the social assistances are repeated, then the recipient does not have the condition to work or the social assistances are not intended to keep the individual on their own; it is “to save the day” (Participant 3). However, what is essential for sustainability is the logic to teach fish (Participant 18).

On the other hand, a third issue is to understand whether abuse is one of the fruits that will arise if the supervision is conducted properly. Most participants think that social policy recipients frequently abuse: “There is someone working at home, the situation of the house is not bad, there is everything such as the internet, household goods are new” (Participant 6). “He has got four flats, but he’s coming to ask for rent allowance” (Participant 5). “She didn’t have any children, but says that she had a baby with a test-tube baby, and ask for allowance” (Participant 32). “Due to the information of her husband passed away, we keep house with her 3 years old child. We are taking them to programs. We are taking him to a picnic, and a year later, you see, there is a big man in the house!” (Participant 4). All these statements point to the presence of recipients who exploit social policy applications. According to some, abuse is multiple; according to some, the abuse is almost half a half (Participant 19). Because of the abundance of abuse, a special name is also used for abusers: “Guest artists”, ie who “visited all districts of Turkey and received social assistance from everywhere” (Participant 16).

Here, another issue comes up. Can getting help from every actor or multiple actors be seen as abuse? An imam says: “One person says he is out. He says he will return to his village when he collects benefit. Then we collect benefit. After that we look at another mosque, that person is still collecting benefit” (Participant 34). It is obvious that the situation in these statements was abused, but if we have a statement like “He needed it, but he collected it from the other mosque because it was not enough to cover his needs”, could it still be called abuse? As stated by one participant, each repetition is not exploit (Participant 13), because it is not really sufficient (Participant 3).

Therefore, as another issue, it is necessary to establish whether there is abuse according to the supervision ensuring that the supervision is successful, instead of provision of the direct abuse of each recipient. Thus, question of “are abusers lazy” would be a reasonable question after we have deduced whether the duplicates are seen as abuse. According to some, it is not reasonable to evaluate the recipients as lazy because it is necessary to know the reasons underlying the issue (Participant 20). There may be those who make charity work like a professional job or those who may become addicted to social assistance like addicts (Participant 30). Except those who abuse this way, it is of course not reasonable to say lazy for recipients who have economic problems or other special situations (Participant 2). If there are people who say “I can’t work on that job, I get a headache, I’m so tired” (Participant 14), it can be said that there is laziness.

In such cases, the punishment comes to mind as the step to be taken. The punishment for the lazy person is the cessation of the supports. For example, as a participant said that “we need to stop social assistance as a state” (Participant 4), stopping the support operations can be the solution. However, the issue should be run differently for those who are abusers, such as misrepresentation, deceit and hiding:

i) First of all, they should be included in the black list. Thus, they should not be supported again (Participant 16).

ii) It may also be possible to cut the support gradually. For example, a needy person who is able to work should be offered a suitable job first. If s/he rejects the job, one or two more alternatives may be offered to him/her; however if the job is rejected or disliked again, the support should be interrupted (Participant 8; Participant 1). This person should not receive any further support.

iii) In some cases, support should be cut immediately after the supervision because the principle of rightness was not followed (Participant 14). As stated, “when the social assistance is stopped, the abusers are standing up to; they reach BIMER, CIMER, 183, District Governor, Governor, Mayor.” (Participant 13) or “they press the organization, and are screaming with the excuse of cutting the support” (Participant 23).

iv) Support should end automatically. An automation system is required for this to be possible. For example, in case of changing social security status, updating of information should be automatic and thus should not receive support (Participant 17).

v) In some cases, the abuser may need to be displayed, but this step may not be desired by some actors (Participant 5). Yet this step is not against compassion; that is not stigmatizing recipients because the problem is about abuse, the issue is not the about recipient but the abuser. Hence, to obstruct the abuser by betraying him/her means compassion to prospective recipients.

vi) The most important issue is the execution of judicial penalties. Just as social policy actors are sentenced to imprisonment in various years for misuse of purpose (Participant 5), some of the social policy recipients should be given prison sentences according to the degree of abuse. After an explanation to the person as “you don’t need any help”, his responding as “if you will write us down, write; otherwise we will get your window down tomorrow” (Participant 32), of course, should require a prison sentence (Participant 18). Otherwise, it will not be possible to prevent such abusers, there will be no deterrence (Participant 14), and therefore bad doubts will arise for real needy people.

Finally, the opposite of the abuser, giving an award to a non-abuser is an act of justice and an indirect penalty to the abuser. For example, a social policy recipient applies to the authorities three months after s/he receives social assistance and says “I don’t need social assistance anymore, give it to someone else” (Participant 19). This situation is admirable and should be worthy of the prize. Awarding is also the education of the rest. This is a consciousness education for every human being on the necessity of not attempting to abuse (Participant 14).

The Possible Obstacles During the Implementation of the Basic Principles and Steps to Overcome the Obstacles

The principles of compassion, justice and rightness alone are not sufficient for the social policy administration of a city because the real issue is the application of these principles. However, there are some grounds for the implementation of the basic principles and it is possible to encounter certain obstacles in the operation of these grounds.

Situations Regarding Relevant Legislation

One of these grounds is related to legislation. The first question to be asked here is whether there is a problem with legislation in terms of social policy administration. It appears that the resulting picture changes according to the perspective. With a participant’s statement, “if you look at the legislation, you don’t do anything; (again) if you look at the legislation, you set out from a sentence and exuberate” (Participant 35). The issue here is that the legislation provides administrators with a variable and relative ground because as stated “our legislation is clear, but we also have a discretion” (Participant 13). Relativity is clearly expressed as follows: “I did never say that I’d have done it if the law allowed it.” (Participant 1). So, the main problem here is what happens when the X administrator changes. Even if there is a problem, the administrator X can perform his/her duties without being stuck in the legislation; X can be replaced by the administrator Y. However, although there is the same legislation, Y may not be able to perform its job properly. Therefore, each administrator does not seek to stretch the problem of legislation or cannot do. The fact that the laws, regulations and similar texts are very diffused in the relevant legislation can also make this kind of stretching work more difficult (Participant 16).

The second issue arising from the mess in the legislation is that there is no common or standard framework. This situation is closely related to the “criteria” of being social policy recipients. Accordingly, the criteria of acceptance as social policy recipients differ for each social policy actor, and this is also due to legislation. There is a different criterion in the municipal actor, in the SYDVs and within the ministry (Participant 2). In social policies of NGOs, applications can be made without relying on any criteria. One of the biggest handicaps of the absence of a common/standard criterion is the duplication (set forth above) (Participant 18); i.e. the problem of being the recipient of multiple actors. It would not be wrong to think that correcting this can solve many of these and similar problems.

When it cannot be corrected, “direction to another actor”, “stretching the law” or “any other” different methods can be put into action as a third issue related to the legislation. Expressions such as “As a solution, we are directing to the municipality, to NGOs or to the district governor or to SYDVs” (Participant 13), “X NGO supports at the point where we are blocked in terms of legislation” (Participant 14), “Even if it does not comply with our legislation, it has complied with the legislation of others” (Participant 2) are examples of a social policy actor “directing” the needy person to the other social policy actor, who can perform applications according to the legislation, when it cannot do the related services due to its own the legislative obstacle. However, sometimes the issue may be in the form of shifting to some risky areas in the sense of disregarding the legislation and connivancing some things from time to time (Participant 12). For example, a social policy actor who does not have the authority to grant direct scholarships according to the legislation may be able to provide support to the students through the criterion of “familial need” by means of other “forms” within the scope of the possibilities offered by the same legislation (Participant 2).

Determination of Social Policy Recipients

Another problematic issue that may arise in the implementation of the principles of social policy administration in a city is related to determining social policy recipients.

In primary care, there is currently an acknowledgment mechanism that is mainly based on the notification of another person or the person’s self application for being one of the social policy recipients. The person either applies to one of the relevant actors or is involved in the process of becoming a social policy recipient upon the notification of NGOs, mukhtar, imam, neighbor or other persons or institutions. It is also possible to reach public social policy actors in some way through other channels such as CIMER and Alo 183 (Participant 13). There are even participants who stated that 90 % of them have reached via internet (Participant 6). The notices are mostly made in order to meet the necessities of the needy during Ramadan (Participant 5). Therefore, firstly it is necessary to enter the process in determining the needy, and this can either be based on notice or application. Ideally, the notification should be minimized and there is a possibility of a “social policy recipient pool” via the automation system without the need for application.

The declarations of the informant or the applicant’s declarations are required in the issue of the determination, but at the same time these statements are risky (Participant 3). In this sense, it is clear that the declaration is not enough (Participant 28); therefore, the second step is taken: Enquiry. It is is bi-directional. One aspect is the “technical enquiry”; ie to scan the relevant person through the automation system. This facility is currently not available in all social policy actors in Turkey. The second aspect is the “social enquiry” in the sense that it is the only contact with the person concerned personally. On the other hand, since the accuracy of the information from the neighbor or environment of the person concerned is not definite and reliable (Participant 2), this information means “preliminary information” in the social enquiry (Participant 6). Interviews in social enquiry can be deep and long at home or as short as 10 minutes (Participant 5). In the assessment, everything in the house is treated as a measure; household items, clothing and so on all variables of the house are taken into account.

Thirdly, perhaps the most important point of determination is the common database for social policy actors. The technical enquiry via the common database can be more reasonable and faster. In particular, considering the problem of abuse (set forth above), it becomes more important for social policy actors to be “together” to determine. When there is no common database, asking the environment, asking the grocery store (Participant 6) or asking someone does not work completely. When this is the case, if there is no possibility of technical enquiry, it is necessary to get help from the people like imam or mukthar who know the public better. Because these segments may be partly “subjective”, there is a risk of determining social policy recipients.

There is also a problem with the criterion as an extension of this issue (also referred to above in the legislation). There are different criteria for each social policy actor. A person supported by one actor may not be supported by another actor due to difference in criteria: “Someone who is in jail and has been released is applying for help. We are investigating him/her. It’s been a year since s/he left prison, but (the other actor) is helping the him/her” (Participant 5). Perhaps more important is that the criteria are not taken into account by considering the difference of the locality. This is a serious disadvantage (Participant 19), because the socio-economic situation of each settlement is different and it will be more reasonable to flex the criteria for this difference. Therefore, on the one hand, there is the problem of differentiating the criteria according to the actors, and on the other hand, the fact that the criteria of the same actor are generally considered without taking into account the settlement.

Budget Constraints

Another issue in the implementation stage of the social policy administration principles of a city is in context of budget.

First of all, there is a known fact that social policy is an area that requires a lot of material power. With the expression of a participant, “these are jobs that require a lot of money” (Participant 10). For this reason, it is often possible to encounter that the budget is not enough. Expressions such as “the money we’ve been spending has gone down” and “there has not been a periodic increase for many years” (Participant 15) reveal the problem. Therefore, it is not possible to do everything in every desired way. As a result of such a problem, for example, it is difficult to completely solve the problem of poverty in a fundamental way (Participant 3). The situation is worse for NGOs. Critical declarations such as “i cannot continue this work because of the impossibilities” (Participant 25) or “we have difficulty paying our rent and our bill” (Participant 26) indicate the depth of the budget problem for NGOs. Therefore, all social policy actors, especially NGOs, have budgetary problems and this situation is experienced more deeply in times of economic problems of the country.

The main point in overcoming this kind of problem is to reinforce budgets or to enlarge it at the beginning (Participant 4): “We need more money” (Participant 23), “because budget means everything” (Participant 3). When no reinforcement or magnification can be achieved, different methods should be introduced. One of these different methods is to carry out activities in the field of social policy “with the support of the relevant units”. The statement of “when a citizen who does not have any furniture in his house apply us, we are directing him to Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality” (Participant 2) should be included here. Support from the Ministry of Youth and Sports is also relevant to this issue (Participant 3); such supports are more project-based (Participant 2). Projects taken from institutions such as Istanbul Development Agency are examples of these (Participant 9). Employers also provide project-based support (Participant 2). Apart from all national support/projects, there may be international support; contribution of the United Nations and other international organizations for Syrians in Turkey (Participant 13; Participant 2) is within this framework. It can also be seen in the form of “sponsorship” to support the activities of social policy actors financially (Participant 26). In addition, a financial source such as zakath is also cited (Participant 15).

Institutional Disorganization and Coordination

The issue also has an institutional ground. First of all, the organizational structure of each social policy actor is different; because one is a municipality, one is a ministerial unit, one is a SYDV and one is an NGO. While the upper unit in an actor may or may not be in the other, the type of personnel in another actor may not be in the other or may be of different type. The unnatural point here is that more than one social policy unit is “under different names” within a public social policy actor. Such a situation can be a problem in the applications. Even though the area of the unit is not related to social policy, its practices may be related to social policy. For example, the municipality has a center called Esenler Social Communication Center (ESTIM). “The main area of this Center is public relations, but its practices are social policies” (Participant 1).

The second issue on the institutional ground is in terms of coordination. This is the most obvious result of the problem in the institutional structure. One aspect of the co-ordination problem is the lack of coordination in the internal organization of a social policy actor, the other aspect of the coordination problem is the lack of coordination between all social policy actors. In other words, social policy units within a social policy actor should not be scattered; if scattered, attention should be paid to the coordination of the relevant units. The coordination of all relevant social policy actors is also important. The issue is more obvious for NGOs. It is the clearest indication they have hard times for finding and seeking simple information to ask and learn (Participant 28). Although it is an automation system, the fact that the municipality is not included in this system causes the social policy actors not to solve the problems they face in practice. What is in this sense is not the coordination but the exchange of information (Participant 6). The situation of social policy recipients is clearly learned through this information exchange, and steps are taken accordingly. In this sense, it is obvious that there is no trouble (Participant 2). However, although this situation may be such a solution-oriented relation at the Esenler scale, the information exchange in each settlement will not be at a reasonable level and will cause problems in the general sense. In other words, the units of general administration and the local administration, ie the social policy actors are coordinated and compatible in Esenler, however his situation is certain for Esenler, while it is not certain for other settlements. It may not be possible to find it in every district. For this reason, it is necessary to set up coordination between social policy actors in a “common database system”; should be all over Turkey (Participant 15). Thus, system-based coordination is essential instead of coordination based on the person (administrator) and the administrator’s grasp of the importance of the work; because the change of administrators requires this.

Therefore, it is necessary to transform the process from person-based to a structural basis. However, since the structure of each settlement will be different, the institutional coordination of the actors should be based on that settlement. As a third issue, R & D activities are important for the social policy actors’ social policy-related institutional structures as well as for improving the quality of practices. At present, it is understood that social policy actors do not have R & D activities (Participant 2; Participant 25; Participant 11; Participant 10). Without R & D, on the one hand, there is a lack of institutional structuring, and on the other hand, there is a problem of coordination among social policy actors. It is essential that R & D exists as an important tool for every social policy actor to avoid or minimize these problems.

Characteristics of the Staff

A sine qua non of social policy administration in a city is related to the staff. First of all, the number of personnel should be checked if they are adequate. Expressions such as “we have no shortage of staff” (Participant 3) or “our current staff is sufficient” (Participant 14) usually continue with “but”s, and signs like “if there were additional staff…” are cited for insufficiency of staff. Essentially, the majority of the participants are suffering from the lack of staff. Due to the lack of personnel, some of the current staff are working overtime (Participant 23), sometimes as a voluntary staff member (Participant 21) closes deficits. Apart from the attempts of existing staff to close lack of personnel, other solutions can be seen. The most obvious of these solutions is to direct recipients to another relevant actor (Participant 12). In addition to this, there may be efforts to solve the problem with personnel support from other units related to the social policy actor. Sometimes intern students can be considered as a kind of staff in the social policy unit (Participant 25). Ultimately, the result is that the social policy-related units of social policy actors are not sufficient in terms of personnel. Therefore, it is necessary to make the number of personnel sufficient. What should be considered here is to adjust the number of personnel according to the population of each settlement and the social policy recipients of the population. Expressions such as “we have 32 employees; of course, this number is not enough for 500 thousand people” (Participant 13) or “the number of our staff by population is insufficient, of course” (Participant 36) explain this logic.

The issue also has a quality aspect. In other words, which qualification should the staff working in the social policy units of social policy actors be? One aspect of this qualification is related to the graduate program/department.

Table 2 – Employees Expected to be Graduated Specific Departments in

Related Institutions of Social Policy in Turkey (Alphabetical Order)

|

|

Department |

Education Year for Graduation |

|

1 |

Child Development |

4 |

|

2 |

Guidance and Counseling |

4 |

|

3 |

Labor Economics and Industrial Relations |

4 |

|

4 |

Medicine |

6 |

|

5 |

Occupational Health and Safety |

2 |

|

6 |

Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation |

2 |

|

7 |

Psychology |

4 |

|

8 |

Social Security |

4 |

|

9 |

Social Work |

4 |

|

10 |

Sociology |

4 |

|

11 |

Teaching |

4 |

|

12 |

Theology |

4 |

Therefore, which department is expected to be more qualified if the personnel working in the related department is graduated? Table 3 provides a basis for this. Graduates from Labor Economics and Industrial Relations, Sociology, Child Development, Psychology, Guidance and Counseling, Medicine, Social Security, Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation and Social Work should be priority and even required because these departments are at the center of social policy (Social Work, Labor Economics and Industrial Relations, Social Security), or are closely related to the field of social policy (Occupational Health and Safety, Sociology, Psychology, Medicine, Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation, Child Development), or contain social policy issues (Theology, Teaching, Guidance and Counseling). The fact that these are priorities in the recruitment of personnel, or that at least a high proportion of staff is composed of graduates of this department mean a positive effect in terms of quality. On the other hand, it is already known that graduates of Sociology, Psychology, Social Work, Guidance and Psychological Counseling are taken as staff (Participant 13; Participant 14). However, the rates of the graduates of the departments listed in Table 3 are low. The more troubling aspect of the issue is the fact that department graduates, who are not from the departments in Table 3, such as logistics (Participant 23), engineering (Participant 17) or who have nothing to do with the social policy area, are also working as staff in the units related to social policy.

On the other hand, there is a tendency not to consider this situation as a direct problem. Even if “maybe it would be much more successful if someone who finished the Labor Economics or any sociologist at my place” (Participant 11) is stated, it is emphasized to try to develop a “different point of view”. In this respect, the importance of point of view is put forward (Participant 18); in other words, the important thing is not a departmental graduation, but to enter the field of social policy, to do the job voluntarily, to love his/her job and to reveal everything. In addition, emphasis on experience comes to the fore. More specifically, it is more important to look at what s/he did, not where s/he graduated. An approach of “is your diploma sociologist or are you a sociologist?” (Participant 1) clearly reflects this. In the end, the issue is shaped both by the relevant department graduation and the experience. The most beautiful and ideal is that the graduate of the department should take into account the experience; because being a remedy for the general disadvantage of social policy recipients requires a serious combination of knowledge and experience.

Such a need, as a third issue, raises the issue of features that personnel should carry.

i) It is important to be alert (Participant 4) because it is possible for social policy recipients (as stated in the above lines) to use the doors of exploitation. This, in one aspect, means dominating the subject.

ii) “S/he must have emotion, but should not be too emotional” (Participant 6) because the intensity of compassion can can cause the balance of justice to be missed. In a way, s/he must emphasize its professional logic.

iii) Inclination to voluntary work is required because dealing with social policy recipients can be hard, and it is sometimes possible for normal operation to fail. In this sense, it should be essential to own the work it does as its own work (Participant 6).

iv) (As an extension of volunteer logic), should be good-humoured because the interlocutor is the victim and they are always in need of sweet words, and smiling faces (Participant 13).

v) (As an extension of volunteer logic), there should be no expectation or interest from social policy recipients. S/he should have understanding of “people pray to us, we don’t want anything else” (Participant 10). S/he should act in a sense of worship (Participant 13), that is, s/he should wait for Allah rather than the receivers for his deeds.

vi) S/he should be fast and agile (Participant 13) because slow operations can increase the grievance of the the victims.

vii) S/he should be visionary (Participant 24). This feature is needed more, especially for the administrators of social policy actors.

viii) Sometimes it is important to be able to speak another language in order to be more useful (Participant 2) because for example, an important issue, such as migrants, is now on the agenda.

ix) (All in total) s/he should be strong. Being strong in body, mind and heart means continuity in work; to maintain coolness (Participant 19).

In order to maintain or improve these and similar qualities, or to bring new positive qualities, it is important to train staff as a fourth issue. One aspect of education is to allow staff to receive training outside the institution. Without giving up for education (Participant 18), giving incentives and permits to graduate students (Participant 16), for example, providing flexibility and getting out of work early (Participant 14) is in this category, or options such as evening education outside the workplace (Participant 11) are included here. The other aspect of education is internal training, ie in-service training. Although in-service training exists, it seems to be weak or inadequate, considering “several times” (Participant 6), “once a year”, “every two or three years” (Participant 16), “twice in five years” (Participant 17). Current in-service trainings can be on issues related to “dialogue with citizens” (Participant 2), “behavior and personal data” or “sitting, getting up, walking” (Participant 4). It’s sort of a way to survive in the field. Ultimately, the in-service training periods should vary according to the unit of staff. Training should be more for field staff, less for top managers.

On the other hand, in-service training means making the staff suitable for the unit (Participant 11); but at the same time, in-service training means giving value to staff (Participant 19). Valuing staff means a solution to the possible burnout problem for the staff. At this point, as a fifth issue, the problem of the burnout of the staff emerges. For example, the staff at the counter, which is one of the first interlocutors with social policy recipients in the SYDVs, deals with 100 people per day (Participant 17). All of what they are interested in naturally expresses their problems. The situation for the field staff can be even more challenging. If the field staff is female, it can also be a challenge. For example, for a woman to go to the home of addicts and to see the situation there is a sense of internal unease (Participant 16). As in the “on the same day we saw two baby funerals. That day, we felt bad until the evening” statement, “feeling bad” is the most frequently described concept. When one of these two babies drowns while they are suckling the mother (Participant 10), there may be a much greater influence on the female staff. Of course, the issue does not only affect the woman, the staff as a father can experience the effects of the event more deeply. The following example is clear: “the father has left, there are a lot of children. Exposure to these scenes is deteriorating. You can’t go home and love your own child, believe me. My child wanted chocolate, for example, recently. I didn’t buy it because those kids come to mind…” (Participant 18). The expulsion from the visited house for the purpose of social enquiry (Participant 4) also affects the staff. Insulting is also possible (Participant 18). Even if there is no bad word or insult, it is considered to have been beaten after a one to two hour review. In summary, the “deterioration” of personnel in the field of social policy (Participant 4) is inevitable.

The critical question here is whether or not personnel have anything to do with this kind of burnout or weariness. According to the interviews, there is no planned, systematic and institutional support in general terms; staff tries to solve their own problems by their own methods; sometimes the administrators have an effort to overcome the problem with their individual efforts. The following statements are clear: “Since we have been working together for 9 years, we sometimes try to solve it among ourselves; or by attending an event together at the weekend” (Participant 2). “There is not much need for rehabilitation because we are used to it” (Participant 16). “We are rehabilitating ourselves” (Participant 14). As can be understood, the problem of the burnout of the staff is tried to be solved by the personnel itself by doing social activities, thinking about a positive part of the job, and getting used to it. As the only step administration involves by changing the position of the staff (Participant 2); therefore this may relieve the staff, even if only for some time. Finally, the ideal step is to ensure the periodic rotation of staff in the field of social policy as well as periodic motivation.

Such a step is also important as a sixth and last issue to keep qualified personnel in the institution because the person who is valued will remain with those who know its value. An indication that the staff is valued is to deal with his/her problems. There are other indicators of dignification. In practice, its special name is “performance assessment”. Doing different treatment among qualified personnel with qualified staff is with the help of justice. There should be a mechanism that distinguishes a staff who graduated from the relevant program, who has the experience about the job, who is fond of doing his job, and the other staff so that the qualified staffs continue in the institution. In addition, wage levels and personal rights are important for all employees. A lower wage or non-paid wage may incur a number of staff outside the organization, because the commitment to the institution in some staff is related to wages. Personal rights also have a similar nature. Having partial arrangements (Participant 17) will only have a partial positive effect.

Social Policy Administration Model of a City Based On Research Findings

Principles of social policy administration in a city are essential, but there may be obstacles in the implementation of the principles. Overcoming these barriers is, in one aspect, a matter of administration. Therefore, the role of actors in the context of administration in social policy implementations constitutes the end point of this article.

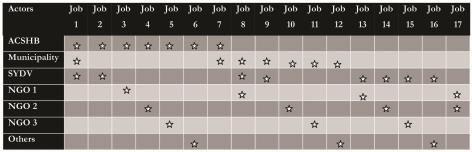

Density Center in Social Policy Recipients

For a reasonable framework in social policy administration, it should first be shown in which context social policy recipients should be addressed.

Firstly, it should be clarified who social policy recipients are. Recipients “of all areas required by disposition” (Participant 1) should be identified. These social policy recipients may be from poor, unemployed, disabled, elderly, women, children, young people, martyr and ghazi, migrant, homeless as well as some special (emergency) groups. There are some issues related to these groups:

i) It is a problem that the “who is poor?” question finds a different response in social policy actors. Each actor of social policy can determine different criteria. Although this may have some benefits, it often seems to be a problem. Therefore, there is a need to establish at least a criterion close to each other. However, because the living conditions in each settlement are different, different criteria should be expected in each settlement. In other words, it is a reasonable criterion among the social policy actors in the same settlement, but it is reasonable to have different criteria for different settlements.

ii) What the unemployed means is standard according to TUIK, however social policy implementations for employment, ie employment policies, are not within the power of every social policy actor.

iii) Since elderly people can be treated in the group of people with disabilities in the sense that they cannot do some things, social policy steps should be taken within the disabled-aged proximity. However, special differences between people with disability and elderly one should not be overlooked.

iv) Not all women may be social policy recipients. Therefore, it is important to differentiate the attitudes and implementations of social policy towards disadvantaged women and non-disadvantaged women. This differentiation is more important for the settlement because the cultural position of women in the regional sense can be effective.